Following the Flock: of Climate change, Mutton and Liver disease

A version of this article was written for Mongabay India on June 13, 2024

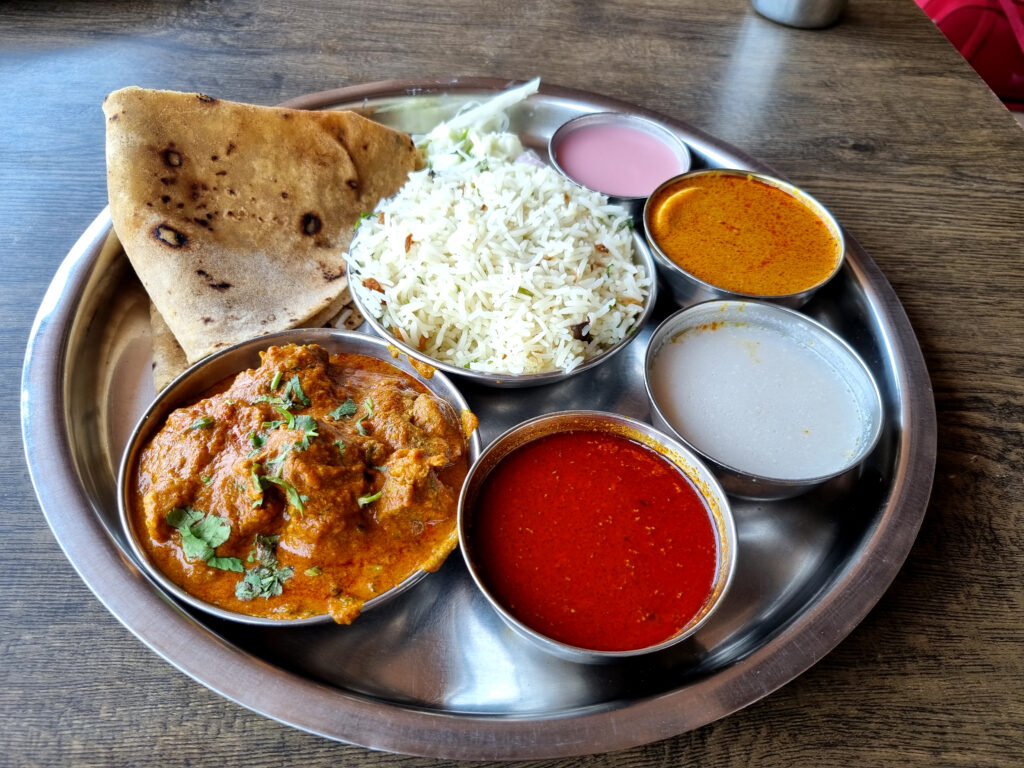

Beyond its seafood, Goa is celebrated for its delicious pork and beef dishes, but not for its mutton, which is considered of an inferior quality. Good mutton if ever encountered in a Goan restaurant generally comes from Kolhapur or Belgavi in neighbouring Maharashtra and Karnataka. In the past, Goans, including myself, would undertake to elaborate, over five-hour road trips to Kolhapur just to savour some spicy succulent Kolhapuri mutton. Fortunately, for those unwilling to venture so far, Wada Kombada, a restaurant in Porvorim along the Mumbai-Goa Highway NH66, which opened nearly two decades ago offers us a close to authentic Kolhapuri dining experience. The owner, hailing from Kolhapur, sources his mutton from there. I frequently visit this place for lunch, particularly for its Kolhapuri mutton thali. This thali is centred around mutton and features mutton sukkha accompanied by two gravies (rassas), both made with mutton stock.

Ironically, as I speak of this small gap in Goa’s rich food culture, every summer over the last three years we have been having unusual sightings of large flocks of sheep grazing off Goa’s fallow fields, particularly along the NH66 not far from Wada Kombada. One hot April afternoon this year while driving along the same highway I happened to spot a large number of sheep in the Guirim fields with two shepherds in their midst – they were back again this year. That same evening on one of our regular evening chai and snack catchups, I took a drive with my friend and environment educator Sujeet Dongre to the fields where I had spotted them earlier that day.

While the odd herd of water buffalo, a few scattered cattle and sometimes pigs are part of Goa’s agrarian vista, large flocks of sheep are a bit of an enigma. The majority of these sheep were of a rust-reddish brown colour, a few white and some black. These were Deccani, one of the several drought-adapted indigenous sheep breeds of India, that, as their name implies, have their origins in the semi-arid Deccan plateau, primarily from the states of Maharashtra and Karnataka. Their bodies were covered with a scant coat of coarse fur rather than wool that at first glance could be easily confused for goats. Not surprisingly they were bred mainly for their meat rather than their wool. I saw Sujeet’s face light up at the sight of sheep. He was a native of the Deccan region as well and spent his childhood in Kamalnagara, a small town in the Bidar district of northern Karnataka, where shepherded sheep flocks, passing his village, were a common sight.

I parked my car beside the highway and we walked over to one of the shepherds who had squatted off the highway keeping a watch over his sheep, who were grazing in the fields below. A lanky white dog covered in red dust sat close by, he had a thick brown string for a collar through which two brass bells were strung, that tinkled when he moved. Being familiar with these communities Sujeet, greeted him in Kannada and began talking to him. His name was Veerappa Dhoni and he told us that he had walked with his family and sheep from Nipani, a town in Karnataka approximately 150 km northeast of these Guirim fields, which was located at the border with Maharashtra and barely 40 km from Kolhapur. He said that he, his family, and his flock covered over 200 km, walking approximately 10-15 km a day and stopping along the way to graze their livestock. For reasons I did not quite understand, Sujeet suddenly switched to speaking to him in Marathi, which was incidentally Veerappa’s mother tongue, although he spoke both Kannada and Marathi with equal fluency. His nomadic life required this from him. He belonged to the Dhangar community. The word ‘dhangar’ itself is derived from the Sanskrit word dhang meaning mountain/hill, literally making Dhangars the people from the hills. More specifically, Veerappa belonged to the clan called the Hatkar Dhangars who are shepherds that lead a nomadic life. Dhangars are among India´s many indigenous communities and could be considered under the broad umbrella term Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IP & LCs). The Centre for Pastoralism (CfP) defines pastoralism as a practice that involves the seasonally mobile management of domesticated animal herds on extensive grazing, with at least 50 percent of household revenues accruing from such animal husbandry. Most of the pastoralists from the Western semi-arid tracts of India rarely own their land.

Veerappa found the Goan farmers were very welcoming and allowed his flock to graze off their fallow fields and also allowed his family to set up camp. Although this is uncommon in Goa, the interdependence of pastoralism with farming communities has been well documented. That said the Dhangars specifically provide penning services to the farmers, that is, in exchange for being allowed to forage on their fields, their sheep provide the service of grazing on the crop residue and weeds, while the sheep dung fertilises the farmers’ fields. Next to agriculture, pastoralism is considered the backbone of the rural economy, contributing to about three percent of the national GDP as well as massively to the food and nutrition security of the country.

As we walked beside Veerappa Dhoni, his approximately 150-strong flock of sheep slowly mowed their way through the still lush grass of Guirim’s fallow field in an orchestrated grazing unison. The few, albeit unruly black goats, disturbed the harmony of the grazing flock, in typical goat fashion, as they skipped and bounded around looking for the odd shrub bush whose fresh flush of leaves, they browsed off. There were also a few horses around, pack animals that carried the make-shift homes of these nomadic shepherds. They limped around the field, their legs bound to prevent them from galloping away. Maintaining an almost invisible corral around this large flock of grazers and browsers were three lanky dogs, their brass bell collars jingling as they ran along the boundaries of the flock, keeping them from venturing onto the highway. The nomadic family had set up camp under a tree at the edge of the field, where they would spend the next few days, before moving to another patch of fallow land.

Despite having evolved in these semi-arid environments, Veerappa explained that the last few years had been particularly hard for him and his sheep. The Dhangars historically have had certain regular migratory routes in the semi-arid region of Western Maharashtra. They begin their migrations well after the monsoons dispersing in search of new pastures and water for their livestock. Poor rains have affected the availability of pastureland and water and are pushing them further away to newer, often uncharted territory. Besides leading to animals dying, they become more susceptible to disease. Another massive ongoing change that has been underway for some years now is the rapid pace of land use change and infrastructure development. Besides fallow agricultural land, the Dhangars graze their sheep on grasslands that were once part of the rural commons. Grasslands constitute what is termed Open Natural Ecosystems (ONEs) which make up a major chunk of the country’s landmass. These areas support a rich diversity of species including several threatened species such as the Indian grey wolf, the great Indian bustard, and the lesser florican among others in addition to conferring a whole host of ecosystem services. Despite this, these grasslands have been often wrongly considered as unproductive wastelands by planners and are subject to largescale reclamation which is leading to a further fragmenting of their forage landscapes and the many other species of wildlife that they share these spaces with.

The Dhangar agro-pastoralists need contiguity in their forage landscapes – the fallow field-grassland commons mosaic, to sustain their nomadic lifestyles and livelihoods. Way beyond their livelihoods, these pastoralists share a deep relationship with their grazing commons, a crucial part of their cultural identity. To them, these landscapes are inter-generational classrooms, where they hone their skills and develop their own rules for sustainable management through treading and grazing lightly and seasonally before moving on to the next patch. Such areas where there exists a close association between specific indigenous communities with their landscape or aquaquape and which are subject to some form of management have come to be known as Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas, also called “Territories of Life”. It is known that although indigenous communities barely make up 6 % of the world population, they are responsible for protecting 80% of the planet´s biodiversity

Last year, 2023, was the second warmest in India since 1901 and one of the five hottest in the past 14 years. This persistent abnormal heat was mainly due to El Niño, a climatic phenomenon caused by unusually warm waters in the Pacific Ocean. El Niño triggers global weather anomalies and has had catastrophic impacts on species and ecosystems. Besides high temperatures, it also affects monsoons, likely shortening the length of the southwest monsoon and causing an uneven rainfall distribution. This year’s El Niño triggered deadly heatwaves in India and possibly severe wildfires in Uttarakhand. High water temperatures led to widespread coral bleaching in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, and the Gulf of Mannar, as corals lose their colour when algae die due to high temperatures. Poor rainfall or late monsoons could further devastate these ecosystems and the vital services they provide.

Moving animals and their parasites

Whether it is the pastoralists with their sheep or other wild species we depend on for food including fish climate-driven migration of animals is now commonplace as local conditions become unsuitable and species are unable to adapt. While the movement of food animals has crucial implications on food and nutrition security and thereby the resilience of regions, there is another pernicious element that is receiving less attention than it should, the spread of disease – zoonoses. While they move particularly under the duress of climate they are prone to infections and parasites

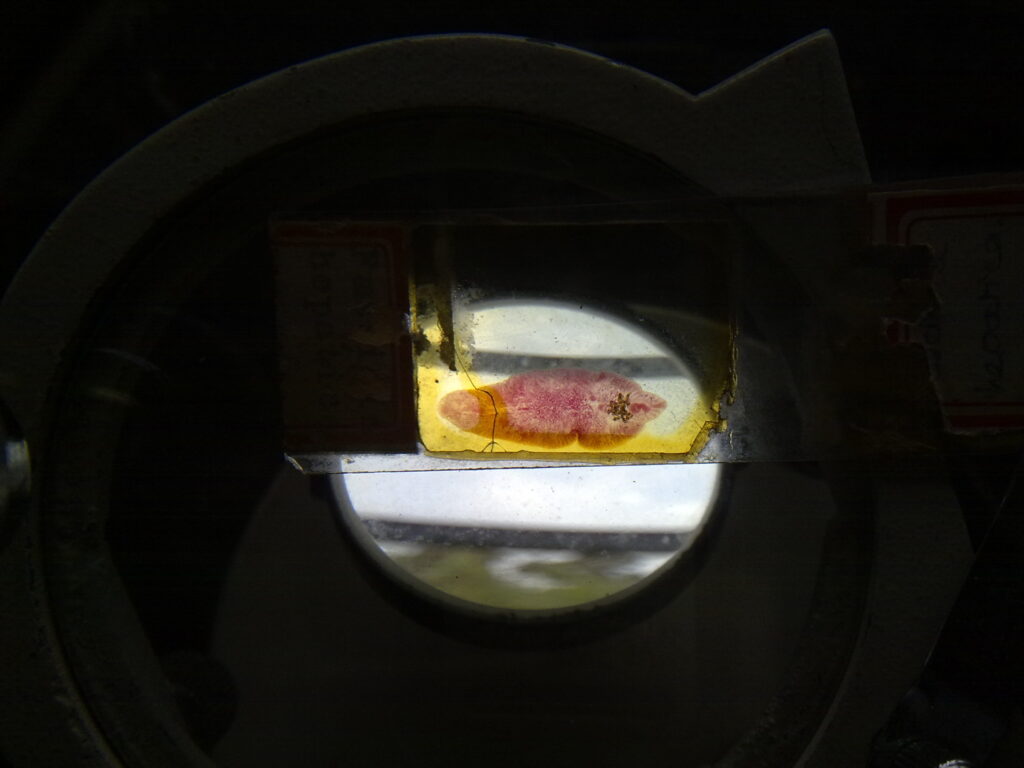

Sheep are often the unwitting, albeit common hosts of a parasite called the liver fluke, responsible for a disease called Fasciolosis, also called the liver fluke disease. Fasciolosis is prevalent worldwide and in India, it is reported to cause huge economic losses in the livestock industry affecting the production of meat and milk and climate change has been documented to drive its spread. The fluke is a small, leaf-shaped parasite living in the liver of sheep, cattle, pigs, and other ruminants. They are hermaphrodites and favour sheep, residing in the bile ducts, feeding on blood, and laying eggs.

As the sheep ate, they dropped pellets (sheep and goat dung) – thousands of them. Considering how common liver fluke disease is, there is every chance these sheep were infected with liver fluke among other parasites. The eggs would be passed through their guts well molded into their pellets. Parched in the summer heat, the dried fluke egg-laden pellets – much like those “seed bombs” – will lie dormant waiting for the monsoons to arrive in early June, bringing the earth to life. Water is a cue for the fluke eggs to hatch, releasing the free-swimming larvae called the Miracidium. The microscopic miracidia swim actively in the water-logged fields propelled by hair-like cilia searching eagerly for their next host – snails, who they have only a limited eight-hour time window to find. Snails are fairly abundant in Goa’s fields emerging in the early monsoons from their summer sleep (aestivation). Within the snail host, the miracidium develop into sporocysts, from which are released large numbers of yet another larval stage called the cercariae. The free swimming cercariae are released from the snail and swim until they find a suitable substrate such as vegetation (which could be vegetables we eat) onto which they attach and form cysts called the metacercarieae. Humans and other mammals become infected by ingesting the vegetation contaminated by these metacercarieae.

Snails (locally called conge) also happen to be a monsoon delicacy that Goan agragrian communities look forward to enjoying. There is however no evidence that people get infected by these fluke parasites on consuming snails. We also currently do not know what the prevalence of these infections in these animals and people look like.

Towards a ´One Health´ Approach

It is known that approximately 60% of the emerging infectious diseases worldwide originate from animals. Infact, some of the deadly outbreaks in the recent past including Ebola, MERS-CoV and COVID – 19 came from animals, facilitated by some of the anthropogenic stressors we place on ecosystems, whether it is through the industrial farming of animals through to driving the loss of biodiversity. It has now become abundantly clear that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and inter-dependent. Because of the multi-sectoral and almost ´wicked´ nature of this problem, four key organizations – the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Health Organization(WHO) came together to form the One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP). The One Health approach which was a result of this panel and takes an “an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems.”

Reflecting on the above, helping solve Veerappa´s hardships could in a way also help prevent the spread of disease and ensure the continued supply of nutritious and delicious food (mutton). Using the ´One Health´ approach will require a multi-sectoral collaboration involving a range of actors including govt departments such as the forest, state biodiversity boards, verterinary bodies, public health, health care, the private sector and most importantly the Dhangars themselves. For this approach to work effectively, capacity will have to be developed beyond the scale of the locale and the state to include counterparts at the regional, national and global levels.

References

Dadas, D. R. (2023). Indian Pastoralism Amidst Changing Climate and Land Use: Evidence from Dhangar Community of Semi-arid Region of Maharashtra. In The Palgrave Handbook of Socio-ecological Resilience in the Face of Climate Change: Contexts from a Developing Country (pp. 85-97). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore

Lalrinkima, H., Lalchhandama, C., Jacob, S. S., Raina, O. K., & Lallianchhunga, M. C. (2021). Fasciolosis in India: an overview. Experimental parasitology, 222, 108066.

Madhusudan, M. D., & Vanak, A. T. (2023). Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi‐arid open natural ecosystems. Journal of Biogeography, 50(8), 1377-1387.